Our head office is in Ottawa—in one of the city’s most distinctive and noteworthy properties.

About our head office

234 Wellington Street

Ottawa, ON, K1A 0G9

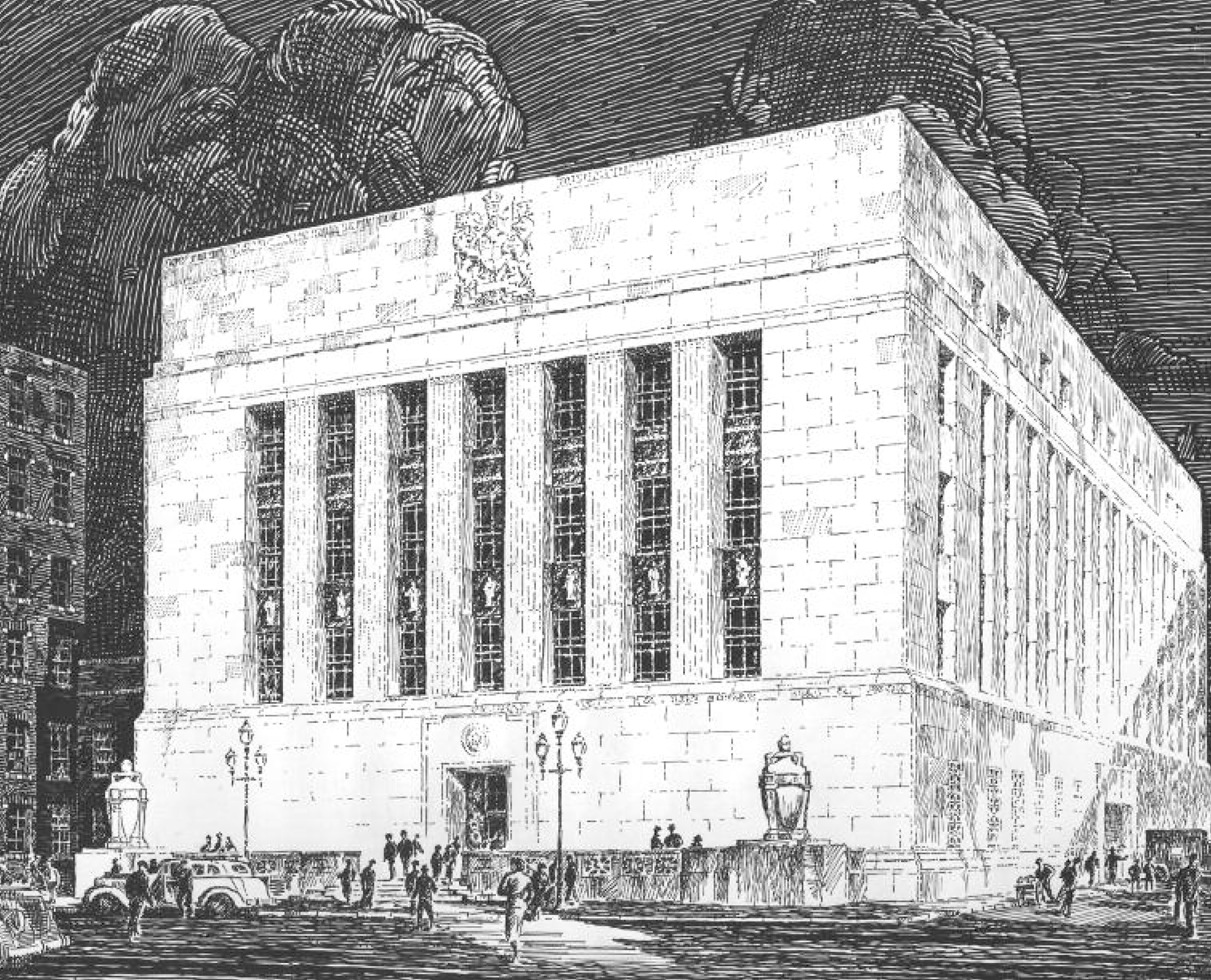

Our head office site is adjacent to Wellington, Bank and Sparks streets. It is known for its unique architecture—a balance of modern and classical styles.

It began in 1938 with the original granite building. Decades later, this classical building was partially enclosed by two modern glass office towers and a large indoor atrium designed by renowned Canadian architect Arthur Erickson.

The site has continued to evolve into a more energy-efficient, agile and collaborative workspace that incorporates granite, steel, glass and concrete materials. The exterior spaces, landscaped for use throughout every season, are popular with employees and the public.

Where we started

Our first home was smaller and humbler.

In March 1935, Bank staff worked in rented offices in the Victoria Building. Conditions quickly grew cramped and inefficient, and in January 1936, Governor Graham F. Towers proposed the design and construction of new premises. Prime Minister Mackenzie King agreed. By May, we had purchased a building site further west on Wellington Street, at a price of $83,500 (about $1.7 million in 2022 dollars).

S.G. Davenport of Montréal was hired to act as consulting architect and adviser for the project. Davenport, in turn, recommended the Toronto firm of Marani, Lawson & Morris as principal architects.

This firm submitted its first designs in May 1936. These were rejected because “they showed a building set in, somewhat in the manner of the Bank of England . . . It is extremely difficult to obtain unity in such a building. The inset part either looks like a chimney, or the whole thing looks like a flower pot in its saucer. The architects more or less agree with us, and are now trying something else.” ‒ Letter from Deputy Governor J.A.C. Osborne to H.C.B. Mynors, July 4, 1936.

In December 1936, the architects presented final drawings of a five-storey, stone-clad building. Its Neo-classical style featured large stone urns beside bronze centre doors and seven tall windows with bronze-and-marble accents. The classical style was popular for banks during the Depression when people sought tradition and solid stability. A substantial underground area accommodated vaults and strong rooms, “all constructed in accordance with the most up-to-date methods.” The plan provided space for a projected staff of 380 people.

Deputy Governor Osborne had reservations about one aspect of the design. He wrote to the Bank of England's B.G. Catterns on February 6, 1937: “You may be somewhat mystified by what appears to be two very large bombs placed each end of the terrace. The façade might, I suppose, look a little weak without these [urns] to balance and pin the building to the ground, but we are not frightfully enthusiastic about them, yet cannot think of anything better....”

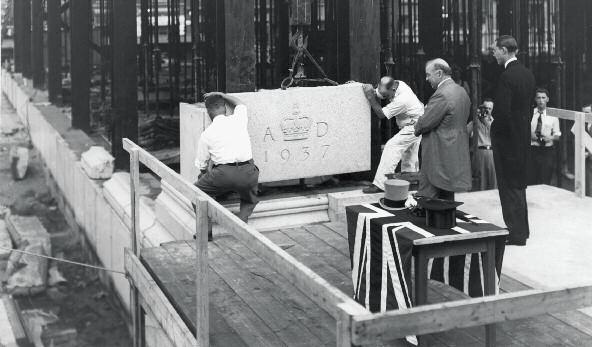

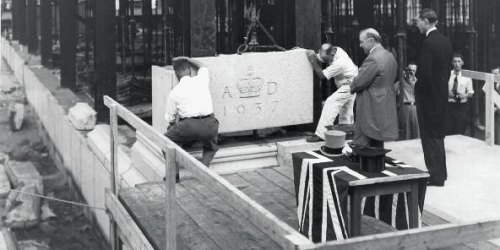

The principal contractor, Piggot Construction Company of Hamilton, Ontario, broke ground in early 1937. Subcontractors from Ottawa, southern Ontario and Quebec worked with them to build with grey granite from Québec. Construction proceeded without any undue delays or cost overruns, and by August 10, 1937, Prime Minister Mackenzie King joined Governor Towers in laying the cornerstone. Staff began occupying the building in 1938.

1940s to 1960s

We quickly outgrew our new building. By 1946, some staff worked in temporary premises scattered around downtown Ottawa. Our executive commissioned Marani and Morris to develop proposals for renovations, but they were never implemented. They tried again in the 1950s, but these too were eventually discarded.

In 1963, the Bank announced that it would host a competition. A shortlist of Canadian architects would be invited to submit proposals for additions to the building. This spurred the Marani firm (then Marani, Morris & Allan) to revisit its earlier proposals, and our Board of Directors found their new design “imaginative and satisfactory.” The competition was cancelled, and in January 1964 we announced our intention to begin construction.

We had to postpone the plans, however. Ottawa in the 1960s was enjoying an unprecedented building boom. The scale of our planned expansion would place undue pressure on the already overburdened construction industry. Late in 1965, Governor Louis Rasminsky announced that we would “defer for the time being the start of construction of our badly needed new head office.”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King (left) and the Bank’s first Governor, Graham Towers (right). A copper box inside the cornerstone contained bank notes of the 1935 and 1937 issues, 1937 Canadian coins, the Bank of Canada Act and the Amendment Act, the By-laws of the Bank, the Reports of the 1st and 2nd Annual Shareholders Meetings, a copy of the Bank’s Statistical Summary for July 1937, a copy of the 1933 Royal Commission on Banking and Currency, which recommended the establishment of the Bank of Canada, and a list of those present at the cornerstone ceremony.

1969 to 2012

By the time we were finally ready to build in the late 1960s, the Marani firm (then Marani, Rounthwaite & Dick) and Arthur Erickson were hired as associate architects to commission a new design. In 1969, they presented a design that preserved the original granite building, partially enclosing it in a vast glass courtyard flanked by two glass towers. The atrium and glass towers spoke to the concepts of transparency and openness favoured by modern central banks.

Construction began in 1972 and continued through the decade. The building was completed in 1979, and staff were fully installed by 1980.

2012 to 2016: Head Office Renewal Project

In 2012, we launched a formal plan to modernize our head office. It was our largest infrastructure project since the glass office towers were built in the 1970s. We consulted with government agencies and members of Canada’s architectural and landscape community on designs for the site.

The design by Perkins+Will Canada preserved and protected the cultural and historical significance of the building while addressing business needs that were not anticipated when the glass office towers were built, such as the widespread use of digital technology and environmental concerns about energy efficiency.

Work on the major renewal began in 2014. The project was completed in November 2016 within its construction budget of $460 million.

We upgraded internal spaces to meet current building standards for

- ventilation, heating, plumbing and electrical systems

- seismic strengthening

- health and safety codes

- accessibility

- energy efficiency and environmental sustainability

- security systems

Modernizing the Bank of Canada’s Head Office

The Bank completed a major renewal of its Ottawa headquarters in 2016.

While the exterior of the centre building was left unchanged, considerable work was done to restore its interiors, which had been modified over time. The original marble lobby on Wellington Street, damaged in the 2010 Ottawa earthquake, was carefully rebuilt and heritage experts were brought in to help restore its art deco ceiling.

Many structural improvements and system repairs were also made to the towers and atrium, though most are not visible. For example, we maintained the exterior aesthetics of Erickson’s reflective glass “curtain walls” but added a layer of interior glass to accommodate upgraded heating and cooling systems.

Erickson’s original design for the atrium, featuring three mounds of Canadian-style greenery and a large pergola, was reinterpreted to create a more versatile space for informal meetings and events. For security reasons, public access to the atrium is limited to special events only.

We modernized our workspaces to meet business needs and to improve efficiency. A variety of meeting rooms and collaborative workspaces complement the open-concept office floors.

The redesigned and landscaped exterior around Wellington, Bank and Sparks streets improved accessibility, safety and functionality. The Bank of Canada Plaza on the property’s east side is available for multi-season use by our employees, Ottawa residents and visitors. Three landscaped pyramid structures provide seating, and two glass ventilation pillars add visual interest and lighting to the plaza.

LEED certification

Our head office achieved a Gold rating in LEED©—that is, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. To attain its certification, we demonstrated excellence in:

- sustainable sites

- water efficiency

- energy and atmosphere

- materials and resources

- indoor environmental quality

- innovation in design

About the Bank of Canada Museum

The design and construction of a reimagined Bank of Canada Museum was a key part of our Head Office Renewal Project. The exhibition spaces, and a conference centre for museum and Bank events, occupy 17,000 square feet underneath the Bank of Canada plaza. It opened to the public in July 2017.

Guests access the Museum through the entrance in the large pyramid on the plaza at the corner of Bank and Wellington streets. Admission is free. Once inside, they can interact with programs and exhibitions to learn about the Bank’s important role in the Canadian economy. Artifacts from Canada’s National Currency Collection are also on display, in keeping with the museum’s origins as the nation’s Currency Museum.

Photos and videos

A collection of photos and videos about the Bank of Canada.

Bank of Canada Archives

A collection of official and amateur photographs in black and white and colour that illustrate the architecture, organization, artwork, functions and interests of the Bank of Canada