Introduction

Good afternoon. It is a pleasure to be with you virtually today.

Thank you, Anita, for that kind introduction, and thank you to all members of the Surrey Board of Trade for welcoming me. My heart goes out to those affected by the recent floods that have been devastating for so many British Columbians.

Canada’s economy has come a long way since the pandemic struck in spring 2020. With high vaccination rates and a broad reopening of the economy, we are well down the road to a full recovery. But we are still feeling the impacts of the pandemic. We have never shut down and reopened an economy before, which makes this recovery unique and complex. The global supply disruptions and related price increases we are experiencing reflect the broader economic forces triggered by the shutdown and reopening of the economy.

Today, I will provide an update on the economy’s progress since our most recent Monetary Policy Report (MPR) in October. I will focus on two issues that are top of mind for many Canadians: supply shortages and the current elevated rate of inflation.

In our last MPR, we discussed the three main drivers of inflation. First, we said about one-third of the high inflation we’re experiencing is due to higher energy prices. Second, the rebound in demand for hard-to-distance services is pushing their prices higher. Finally, the supply constraints have increased the prices of many components of the CPI basket, most of them tied to goods.

I will elaborate on this last driver and discuss why we believe inflation will ease over time as supply catches up. I will also talk about how the two issues I mentioned earlier factored into our interest rate decision yesterday. Specifically, I’ll explain how the Bank of Canada assesses the risks to our forecast for inflation and how we adjust our forecast when those risks materialize.

Supply constraints

I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say most of us have had a recent experience with supply chain disruptions. Whether you have been looking to buy a car or a dishwasher, or are shopping for family ahead of the holidays, the reality is that some goods are not available and wait times are longer.

These supply shortages aren’t just affecting Canada; they are a global phenomenon largely related to the unique circumstances of the pandemic. Strong demand for goods, combined with multiple supply shocks, is feeding through to business costs and resulting in higher prices. Let me talk about how demand interacted with supply constraints before I turn to the impact it has had on prices.

Simply put, the pandemic threw the global economy into a series of successive lockdowns and other health measures, which disproportionately impacted hard-to-distance services. These pandemic closures also significantly altered household consumption patterns. During the pandemic, people spent more on goods such as groceries and household appliances and less on services.1

After the initial wave of the pandemic, spending on goods recovered much more quickly than spending on services. Spending on goods had more than fully recovered by the third quarter of 2020, to roughly 5 percent above its pre-pandemic level. This rapid rebound in goods consumption was underpinned by fiscal and monetary policy. Government support programs and ultra-low interest rates kept many workers employed and kept access to credit and buying power intact. While consumption of services started to recover around the same time, it remained roughly 12 percent below its pre-pandemic level through to the beginning of 2021. Only recently have we seen a meaningful increase in services consumption, but it is still 4 percent below where it was before the pandemic.

An important consequence of this shift in consumption patterns, observed in most advanced economies, is that it put extraordinary strain on global shipping networks. Since so many goods and their components are traded, the demand for shipping containers to carry them increased; ports, rail and trucking services came under pressure; transportation costs rose; and shipping delays intensified.

These bottlenecks and delays were amplified because many businesses responded to shortages by ordering their inputs not only earlier, but also in greater quantities. With demand stronger than what would be expected under normal business conditions, this so-called bullwhip effect further exacerbated supply strains.

The impact of these bottlenecks has fed through to a wide range of manufacturers that depend on imported parts and materials. Firms couldn’t secure key inputs in a timely manner, and many slowed or even stopped production, causing additional backlogs, supply constraints and delays. Canadian manufacturers saw their suppliers’ delivery times lengthen to near-record levels by November.

On top of those related to the pandemic, we’ve seen other disruptions to supply, such as bad weather affecting crop harvests in many parts of the world, including the harvests of our western grain farmers.

Labour shortages are also contributing to the supply shock. In addition to pre-pandemic shortages of highly skilled workers, we have also faced elevated vacancy rates for jobs in the service sector. It takes time for companies to find workers with the right skills and for workers to find the right jobs.

This demand-supply imbalance has resulted in higher inflation. Many components of the CPI basket have been subject to supply constraints, most of them tied to goods. The average inflation rate of goods in 2021 has been 4.4 percent, much higher than that of services at 2.1 percent. This is in sharp contrast to historical trends, whereby services have typically experienced higher inflation than goods. In the 20 years before the pandemic, goods inflation was only 1.4 percent on average and inflation for services was 2.4 percent.

We expect supply disruptions to unwind over time. Bottlenecks will be resolved, so supply should catch up. At the same time, we anticipate some companies will be motivated to add to their capacity to meet demand over time—by expanding their factories, investing in new technologies and automation, and hiring more workers. Others may adapt by modifying their products to get around shortages and reduce high input costs.2 Logistics companies will also add shipping capacity.

Consumers can also be expected to resume spending a more typical share of their income on services. This was evident recently, with a sharp increase in spending on hard-to-distance services in the third quarter. Consumers may also shift away from products that are not available to those that are, which would lower demand for goods in short supply.

However, this risk that supply disruptions persist longer than we expect figured prominently in our deliberations leading up to yesterday’s policy decision. So, I’ll turn to how we have been assessing this risk and how we adjust our forecast when a risk materializes.

Risks to our outlook and adjusting to incoming data

Given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and the uniqueness of the recovery, evaluating the risks to our outlook has taken on more importance.

Central banks must assess where the economy and inflation are heading, since monetary policy actions take time to flow through the economy and achieve their desired result. Nonetheless, even in normal times, there is always a degree of uncertainty when measuring economic activity as well as gauging underlying inflationary pressures related to the output gap and other factors. Our models provide a valuable framework upon which to build our forecast, but they reflect historical economic trends and cycles and can’t capture all economic realities. Given that there is no historical precedent to the sudden closing and reopening of the economy, our models were not built to capture the many economic forces that arose from the pandemic.

We routinely list key risks to our inflation outlook in the MPR to help people understand the factors that could affect inflation and the uncertainty around the outlook. We examine incoming data to help us update our assessment of whether a risk is materializing, and then we update our baseline forecast accordingly—taking on board all or part of that materialized risk or removing it if it’s no longer a factor.

At the beginning of the year, we saw evidence of semiconductor shortages affecting the production and sales of motor vehicles. The production of motor vehicles and parts fell by close to 15 percent during the first half of the year. Additional supply constraints started to become apparent as COVID-19 outbreaks further disrupted production of other goods in some countries.

From there, evidence of transportation bottlenecks mounted with ocean shipping costs and port delays climbing in the spring. Then challenges sourcing parts started affecting exports, investment and inventories. What had begun as a narrow set of supply constraints, largely centred on vehicles, started to grow and come together into a generalized supply shock that interacted in myriad ways with robust demand for goods.

It became more apparent over the summer that the situation had evolved considerably, and supply constraints had become much more prevalent. Supply chain disruptions suggested a significant, negative impact on productive capacity.

Firms we spoke to in our Business Outlook Survey leading up to our October decision said that supply chain disruptions were more prevalent and had worsened since earlier in the year. These businesses also expected the disruptions to persist into the second half of 2022. An unusually large portion of respondents said they would have difficulty meeting an unexpected increase in demand, with roughly one-third of firms mentioning the supply chain as a bottleneck, up from less than 10 percent before the pandemic.

We took this information on board in our October forecast and drew heavily on our past experience to guide our assumptions about the magnitude and persistence of the effects of supply disruptions on economic activity and inflation.3 Overall, our analysis suggested the supply factors were holding back productive capacity by more than their impact on demand, suggesting the output gap was likely narrower than projected in July.

The pandemic’s unusual nature makes it hard to pinpoint when the impact of these supply disruptions will peak. In October, we estimated that this would happen sometime toward the end of 2021, before gradually dissipating over 2022. But gauging how quickly supply issues will be resolved—and hence how much productive capacity exists compared with demand—is difficult.

As a result, we are looking at a wide range of data, including labour market indicators, to assess the amount of slack in the economy, and our decisions will increasingly depend on how these data evolve.

Our decision yesterday

So where do things stand now? Let me first turn to some good news.

Last week’s Labour Force Survey provided a very strong indication that Canada’s job market has largely recovered in most sectors. Workers have rejoined the workforce, notably in the service sector, and companies have hired to meet demand. On top of this, job vacancies across the country are near record highs.

Moreover, since our most recent report in October, economic data continue to show a rebound in activity associated with reopening the economy. Third-quarter GDP data showed impressive consumption-led growth of 5.4 percent—in line with our October forecast. That said, the level of GDP was still about 1½ percent below where it was at the end of 2019 before the pandemic began. And the flooding in British Columbia is likely to temporarily weigh on growth in the fourth quarter.

However, in terms of supply constraints and inflation dynamics, the picture remains mixed. While there are early signs that some supply constraints are easing, such as for semiconductors, most constraints remain largely unresolved. Moreover, as Governing Council noted in this week’s policy discussions, the floods in British Columbia are likely to worsen backlogs at the Port of Vancouver and disrupt shipping by rail and truck.

Then there is the Omicron variant. We expect to learn more about how this will impact public health and the economy in the weeks to come. Hopefully, Omicron will turn out not to be too serious, but there is a risk that it could hold back services consumption. In terms of Omicron’s effects on inflation, the new variant has triggered a sharp drop in oil prices in the near term. But further out, given its potential to restrain the transition to more balanced consumption patterns between goods and services, it could exacerbate upward price pressure on the goods that are experiencing supply constraints.

This only serves to reinforce my earlier point that gauging how quickly supply issues will be resolved—and hence how much productive capacity exists compared with demand—is challenging. The degree of excess supply and demand varies across sectors, which means our typical measure of slack comes with a higher degree of uncertainty.

Supply chain disruptions and related cost pressures continue to be an important upside risk to our inflation forecast. Our current view remains that we should see elevated inflation subside in the second half of next year. However, we will conduct a full assessment of this risk in January when we update our projection for the economy and inflation.

And that’s why yesterday we maintained the policy interest rate at the effective lower bound of 1/4 percent and maintained the Bank’s extraordinary forward guidance.

Governing Council judges that in view of ongoing excess capacity, the economy continues to require considerable monetary policy support. We remain committed to holding the policy interest rate at the effective lower bound until economic slack is absorbed so that the 2 percent inflation target is sustainably achieved. In the Bank’s October projection, this happens sometime in the middle quarters of 2022. We will provide the appropriate degree of monetary policy stimulus to support the recovery and achieve the inflation target.

Conclusion

There is much to be hopeful for as we move closer to a full recovery. Many public health restrictions have been lifted, although new variants remain a cause for concern. People are getting back to work, and companies are investing to meet growing demand.

Nevertheless, the unique circumstances of this recovery present important challenges. With CPI inflation considerably above our target range of 1 to 3 percent, the materialization of upside risks is of greater concern. If supply disruptions and related cost pressures persist for longer than expected and strong goods demand continues, this would increase the likelihood of inflation remaining above our control range. This could feed into inflation expectations and contribute to wage pressures, leading to a second round of price increases. However, medium- to long-term inflation expectations remain well anchored. Meanwhile, wage increases have picked up, but to pre-pandemic levels.

From the early days of the pandemic to more recently, as our economic recovery has progressed, we have adjusted monetary policy to provide the appropriate amount of stimulus the economy has needed. In early November, we ended our quantitative easing program. With the economy once again growing robustly, we judged that this extra layer of stimulus was no longer required.

While we expect inflation to ease in the second half of next year, we are closely watching inflation expectations and labour costs to ensure that the forces pushing up prices do not become embedded in ongoing inflation. Rest assured that the Bank of Canada remains resolute in its commitment to keep inflation under control.

Thank you.

I would like to thank Brigitte Desroches and Michael Francis for their help in preparing this speech.

Related information

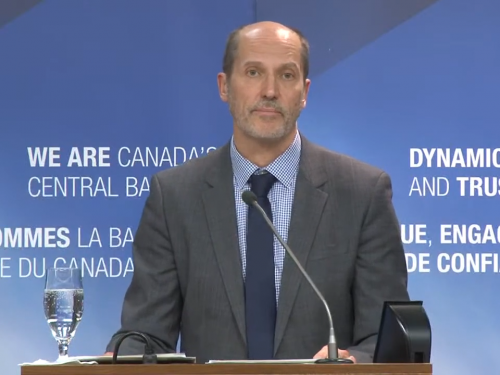

Speech: Surrey Board of Trade

Economic Progress Report — Deputy Governor Toni Gravelle speaks by videoconference (14:00 (ET) approx.).

Media Availability: Surrey Board of Trade

Economic Progress Report — Deputy Governor Toni Gravelle takes questions from reporters by videoconference following his remarks (15:15 (ET) approx.).