Introduction

In Canada, 39% of households have a mortgage (Statistics Canada 2024). For these households, mortgage payments typically represent their single largest regular expenditure. Ensuring that households can make these payments is critical for financial stability because nonpayment can lead to credit losses for lenders. To improve the resilience of the mortgage market, and the banking system more generally, regulatory authorities have for over a decade required federally regulated lenders to perform mortgage stress tests, a form of macroprudential policy.

Put simply, mortgage stress tests assess whether households have sufficient flexibility in their budget to make larger mortgage payments than what is determined by their financial institution when they sign a mortgage contract. Households must demonstrate they can sustain mortgage payments calculated using, in most cases, a higher mortgage interest rate than the one offered by lenders on their proposed contract. This additional financial flexibility could likely help households cope with either a reduction in income or an increase in expenditures such as mortgage payments.

From the 2010s onward, the Government of Canada and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) introduced successive policies that gradually led to most mortgage originations by federally regulated financial institutions (FRFIs) being subject to stress tests. The two major policies involving the stress tests were implemented in 2016 and 2018. From a research standpoint, they provide an interesting opportunity to evaluate the impact on mortgage markets and house prices. This analysis not only assesses the intended effects of the implemented policies, but also expands the evaluation to multiple indicators, offering a broad understanding of the impact of such policies.

In the spring of 2022, the Bank of Canada and other central banks started to significantly raise policy interest rates, which led to substantially higher mortgage interest rates. This situation offers a similarly valuable opportunity to assess the impact of mortgage stress tests on the financial resilience of Canadian mortgage borrowers to higher interest rates.

Leveraging data on mortgage originations, we find that mortgage stress tests, when applied to most mortgage purchase originations, improve credit quality and reduce both credit growth and house price growth. They also improve the resilience of borrowers to financial shocks, such as the large increase in interest rates over the 2022–23 period.

In particular, we show the following:

- The 2016 mortgage stress tests—a policy implemented only for insured mortgages—resulted in an improvement in standard measures of credit quality for new mortgages, such as credit scores and the distribution of loan-to-value (LTV) and debt service ratios. However, due to its narrow scope, this policy had a limited impact on the mortgage market because it did not contribute to slowing down growth in mortgage credit and house prices in Canada.

- The 2018 mortgage stress tests—a policy implemented for uninsured mortgages—improved credit quality across the entire mortgage portfolio, as intended. But it also had broader implications since it led to lower mortgage credit and house price growth.

- In the context of the monetary policy tightening that started in March 2022, mortgage stress tests are effective in ensuring that households can successfully manage increases in mortgage payments without falling behind on their credit obligations. Specifically, following the rise in the Canadian policy interest rate, geographical areas more exposed to the 2016 policy experienced a lower increase in credit delinquencies than less exposed areas did. This difference is particularly pronounced for delinquencies on credit cards and auto loans and for borrowers holding mortgages with LTV ratios above 80%.

The mortgage stress tests

In Canada, residential mortgages are generally subject to robust underwriting practices and regulatory constraints aimed at increasing the likelihood that borrowers are able to repay their debt obligations. This ability is formally assessed through calculation of two debt service ratios, namely:1

- the gross debt service (GDS) ratio—the share of income devoted to mortgage payments and other housing costs (such as property taxes, heating costs and condo fees, if applicable)

- the total debt service (TDS) ratio—the share of income allocated to all (both mortgage and non-mortgage) debt payments and other housing costs

Insured mortgages face limits on GDS and TDS ratios of 39% and 44%, respectively. Mortgage stress tests change how these debt service ratios are computed. For mortgages subject to the stress tests, debt service ratios are calculated using a rate (the stress test rate) that may be higher than the contractual one. While the stress test rate does not directly affect mortgage payments, it results in higher qualifying debt service ratios, potentially limiting the maximum loan amount for which a borrower can qualify or requiring a larger down payment.

As detailed in the June 2018 Bank of Canada Financial System Review (Box 1), the policies for stress testing government-backed insured and uninsured mortgages were characterized by the following:

- Before 2016, the Government of Canada and OSFI mandated stress tests to be applied to high- and low-ratio mortgages, either with variable rates or with fixed rates with terms of less than five years.

- From October 2016 onward, the Government of Canada expanded the scope of stress tests to include all government-backed insured mortgages.

- From January 2018 onward, OSFI issued an update to Guideline B-20, requiring FRFIs to stress test uninsured low-ratio, fixed-rate mortgages with terms of five years or more. In other words, banks were required to underwrite these mortgages based on stress-tested debt service ratios, despite these mortgages not being subject to the regulatory limits described above.

The stress test rate, also known as the minimum qualifying rate (MQR), was also modified over time:

- Before January 2018, it was the higher value between the contractual rate and the MQR floor (the mode of the five-year mortgage rates posted by the Big Six Canadian banks2) for all mortgages subjected to stress tests.

- After January 2018, it was the higher value between the contractual rate plus 200 basis points and the MQR floor for all low-ratio mortgages. For high-ratio mortgages, the stress test rate remained the higher value between the contractual rate and the MQR floor.

- After June 2021, the MQR floor was set at a fixed value of 5.25% for both high- and low-ratio mortgages (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Policy rate and minimum qualifying rate floor

The data

The analysis in this note relies on three primary data sources:

- Loan-level mortgage origination data from most entities regulated by OSFI—This dataset encompasses approximately 80% of all new mortgage originations by volume (Crawford, Meh and Zhou 2013) and includes various mortgage characteristics, such as month of origination, outstanding balance, contractual interest rate, LTV ratio at origination, GDS and TDS ratios, mortgage type and amortization period. Additionally, it provides borrower characteristics, such as income at origination and location by forward sortation area (FSA).3 Given the purpose of this study, we limit the analysis to mortgages associated with new purchases and exclude portfolio insured mortgages. Consequently, the insured mortgages in our dataset correspond to high-LTV mortgages, while uninsured mortgages correspond to low-LTV mortgages. For simplicity, we use the terms high-ratio and low-ratio throughout the rest of this note, rather than insured and uninsured mortgages.

- Credit history data from TransUnion (one of the two credit reporting agencies in Canada, which covers nearly the entire Canadian population)4—This monthly longitudinal panel dataset has a broad coverage of borrowers’ liabilities (credit products such as mortgages, auto loans, credit cards and lines of credit) and includes various credit product characteristics, such as credit histories and limits, balances, payments and delinquency status. It also provides borrower characteristics, such as age, credit score and location (FSA).

- FSA-level house price indexes from Teranet–National Bank—These indexes use a repeat-sales methodology (excluding properties sold only once) and are constructed by measuring price changes between sales of the same property across different time periods. These price indexes remain unaffected by changes in property characteristics or quality. Such indexes are also used by federal banking regulators to assess housing market conditions.

In our analysis, we aggregate borrower-level data by location. For urban areas, a location is defined by census agglomeration, roughly corresponding to a city. For rural areas, a location is the FSA.

The 2016 and 2018 policies on mortgage stress tests

The policies implemented in 2016 and 2018 were expected to alter the behaviour of both borrowers and lenders. If new mortgages had exhibited the same characteristics as mortgages issued before the policy adjustments, some of them would have exceeded the qualifying TDS ratio threshold of 44%. To illustrate this point, we compute a counterfactual TDS ratio for all mortgages issued in the 12‑month periods preceding and following each policy. For this purpose, we calculate the counterfactual mortgage payment using the new MQR imposed by the policy.5

Chart 2 plots results for the October 2016 policy, which affected only the high-ratio mortgages. The blue bars depict the full distribution of the counterfactual TDS ratio for high-ratio, fixed-rate mortgages with terms of five years or more issued from October 2015 to September 2016. The vertical red bar represents the 44% TDS ratio. This plot reveals that 26% of the high-ratio mortgages issued within the 12-month period before October 2016 would have failed to qualify under the new rules. In contrast, the black hollow bars show the qualifying TDS ratio for the high-ratio mortgages issued between November 2016 and October 2017. It suggests that the introduction of the mortgage rate stress tests was constraining: virtually no mortgages were issued with a qualifying TDS ratio above the regulatory limit.

Chart 2: Total debt service ratios for high loan-to-value mortgages—2016 policy

Chart 2: Total debt service ratios for high loan-to-value mortgages—2016 policy

Note: The blue bars plot the distribution of the counterfactual total debt service (TDS) ratios for mortgages issued between October 2015 and September 2016 under the new rules implemented in October 2016. The black-outlined hollow bars plot the distribution of the qualifying TDS for mortgages issued between November 2016 and October 2017. The vertical red bar represents the 44% TDS ratio. Only high loan-to-value mortgages are considered.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2017

We repeat the same analysis for mortgage issuances in the 12 months before and after the January 2018 policy (Chart 3). Since high-ratio mortgages were already affected by the 2016 policy, in panel b, we observe minimal differences between the qualifying TDS ratios reported by OSFI and the counterfactual TDS ratios computed using the method described above.6 In panel a, we plot the distributions of counterfactual TDS for low-ratio mortgages using blue bars. We see that 29% of low-ratio mortgages issued between January 2017 and December 2017 would have had a TDS ratio above 44% under the new rules introduced the following month. For low-ratio mortgages issued after January 2018, the black hollow bars show that 13% of these mortgages were issued with a qualifying TDS ratio above 44%. This share exceeds its post-policy counterpart for high-ratio mortgages since, rather than having a single TDS ratio cut-off, low-ratio mortgage originations are subject to FRFIs’ stated risk appetite. However, this share is below the level it was in 2018, indicating that, despite not being binding, the TDS ratio limit of 44% remains a significant factor in mortgage qualification for high-equity mortgages.

Chart 3: Total debt service ratios for mortgages—2018 policy

Chart 3: Total debt service ratios for mortgages—2018 policy

a. Low loan-to-value ratio mortgages

b. High loan-to-value ratio mortgages

Note: In each panel, the blue bars plot the distribution of the counterfactual total debt service (TDS) ratios for mortgages issued between January 2017 and December 2017 under the new rules implemented in January 2018. The black hollow bars plot the distribution of the qualifying TDS for mortgages issued between January and December 2018. The vertical red bar represents the 44% TDS ratio.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: December 2018

In the analysis that follows of both high- and low-ratio mortgages, we refer to the blue area to the left of the red line (Chart 2 and Chart 3) as the disqualified share. This represents the share of mortgages issued during the 12-month period before the policy implementation that would fail to qualify if the new rules were already in place. We can also compute this share across different geographical locations, c, defined as:

\(\displaystyle\, Disqualified\ share_c =\) \(\displaystyle\, \frac{Number\ of\ mortgages\ that\ would\ fail\ to\ qualify\ under\ the\ new\ policy_c} {Number\ of\ mortgages\ issued\ before\ the\ policy\ change_c}\) \(\displaystyle\, (1)\)

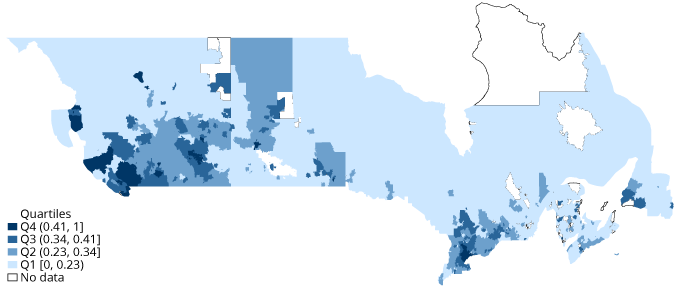

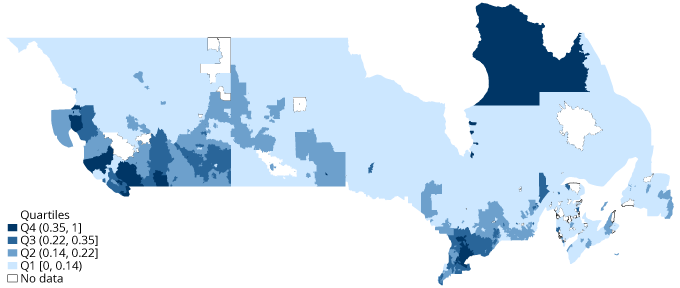

Figure 1 displays regional variation in the disqualified shares for the 2016 and 2018 policies. Given that the two policies target different types of mortgages, the exposure to each differs by location. As expected, the 2018 policy had a stronger impact in the greater Toronto and Vancouver areas than the 2016 policy did.

Figure 1: Disqualified share by geographical location

Figure 1: Disqualified share by geographical location

a. 2016 policy

b. 2018 policy

Note: The maps plot the disqualified share defined in equation (2) for each location in Canada. In the quartiles, round parentheses indicate the end point is excluded; square brackets indicate the end point is included. For example, (0.41, 1] is the set of all numbers between 0.41 and 1, excluding the 0.41 and including 1.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: December 2017

Table 1 presents summary statistics characterizing the disparity between the least and most exposed locations. For both policies, the most exposed areas (those with a disqualified share above the median) exhibit higher LTV ratios and lower incomes and credit scores, on average, than the least exposed areas. Additionally, for the 2018 policy, the most exposed areas also experienced higher house price growth than the least exposed ones. However, we observe no significant differences in terms of TDS, GDS, payment-to-income ratios, or the average amortization periods and mortgage rates.

Table 1-A: Summary statistics for the 2016 policy

| Below-median disqualified share | Above-median disqualified share | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | Mean | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | |

| Number of mortgages (thousands) | 386.37 | 386.37 | 386.37 | 203.12 | 203.12 | 203.12 |

| Mortgage amount (thousands) | 332.25 | 176.8 | 422.5 | 281.27 | 181.3 | 355.67 |

| LTV (%) | 71.34 | 65 | 80 | 94.18 | 92.16 | 97.44 |

| Effective TDS ratio (%) | 33.99 | 28.04 | 40.16 | 33.3 | 29.27 | 38.05 |

| Effective PTI ratio (%) | 15.99 | 9.52 | 21.75 | 17.82 | 13.15 | 22.59 |

| Effective GDS ratio (%) | 24.94 | 17.17 | 32.35 | 25.01 | 19.26 | 31.33 |

| Amortization (years) | 26.49 | 25 | 30 | 24.2 | 23.83 | 25 |

| Mortgage rate (%) | 2.66 | 2.35 | 2.79 | 2.66 | 2.49 | 2.79 |

| Income (thousands) | 126.86 | 71.44 | 156.19 | 95.19 | 63 | 115.33 |

| Credit score | 769.17 | 734 | 812 | 747.31 | 708 | 787 |

| House price index nominal growth (%) | 4.28 | .24 | 8.34 | 3.94 | .24 | 8.34 |

| House price index real growth (%) | -9.14 | -13.18 | -5.08 | -9.48 | -13.18 | -5.08 |

Note: LTV is the loan-to-value ratio. TDS is the total debt service ratio and GDS is the gross debt service ratio. PTI is the payment-to-income ratio. Data are monthly observations from October 2015 to September 2016.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Teranet-National Bank and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: September 2016

Table 1-B: Summary statistics for the 2018 policy

| Below-median disqualified share | Above-median disqualified share | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | Mean | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | |

| Number of mortgages (thousands) | 385.36 | 385.36 | 385.36 | 180.06 | 180.06 | 180.06 |

| Mortgage amount (thousands) | 336.29 | 180 | 432.29 | 285.03 | 180.8 | 360.85 |

| LTV (%) | 71.22 | 65 | 80 | 94.14 | 92.16 | 98.17 |

| Effective TDS ratio (%) | 33.58 | 28.3 | 39.11 | 32.41 | 28.94 | 36.75 |

| Effective PTI ratio (%) | 16.31 | 9.9 | 22.24 | 17.52 | 13.07 | 22.32 |

| Effective GDS ratio (%) | 25.93 | 18.26 | 33.36 | 25.83 | 20.09 | 32.2 |

| Amortization (years) | 26.06 | 25 | 30 | 24.16 | 23.58 | 25 |

| Mortgage rate (%) | 3.01 | 2.59 | 3.35 | 3.02 | 2.59 | 3.34 |

| Income (thousands) | 130.87 | 75.06 | 161.62 | 101.18 | 67.74 | 122.56 |

| Credit score | 776.65 | 740 | 820 | 753.66 | 714 | 795 |

| House price index nominal growth (%) | 6.4 | 1.27 | 11.22 | 8.05 | 1.09 | 15.28 |

| House price index real growth (%) | 1.22 | -3.92 | 6.04 | 2.87 | -4.1 | 10.09 |

Note: LTV is the loan-to-value ratio. TDS is the total debt service ratio and GDS is the gross debt service ratio. PTI is the payment-to-income ratio. Data are monthly observations from January 2017 to December 2017.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Teranet-National Bank and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: December 2017

To formally assess the impact of these changes in macroprudential policy, we leverage the differences in the disqualified share across locations by employing a difference-in-differences approach.7 We analyze the direct effects of macroprudential policies on the mortgage market and house prices by estimating the following empirical specification using ordinary least squares:

\(\displaystyle\, Y_{c,t}\) \(\displaystyle=\, \beta_0\) \(\displaystyle+\, \beta_1\ Disqualified\ Share_c\) \(\displaystyle ×\, Post_t\) \(\displaystyle+\, θ_c\) \(\displaystyle+\, γ_{p,t}\) \(\displaystyle+\, ϵ_{c,t}\) \(\displaystyle,\, (2)\)

where:

- \(\displaystyle\, Y_{c,t}\) denotes the local aggregate outcomes of interest for location\(\displaystyle\, c\) at time\(\displaystyle\, t\), e.g.:

- effective TDS ratio8

- number of mortgages

- mortgage size

- credit score

- LTV ratio

- purchase value

- aggregate growth in local house prices

- the\(\displaystyle\, disqualified\ share_c\) is defined in equation (1)

- \(\displaystyle\, Post_t\) is a dummy variable that takes the value of one in the 12 months following the policy implementation and zero in the 12 months preceding it9

- \(\displaystyle\, θ_c,\) denoting location fixed effects, controls for persistent differences across locations and ensures that all results are estimated using within-location variation in the variable of interest.10

- \(\displaystyle\, γ_{p,t}\) denotes province-by-time fixed effects, which control for province-level trends in mortgage and housing markets, province-level aggregate shocks and aggregate shocks such as changes in monetary policy11

In this empirical specification, the main coefficient of interest is \(\displaystyle\, β_1\). If\(\displaystyle\, β_1\) is statistically different from zero, it indicates that the policy implementation induced a change in behaviour in locations more exposed to the macroprudential policy (with a higher disqualified share) that differs from the behaviour change induced in less-exposed locations.

Table 2 reports the qualitative results of estimating equation (2). (More detailed quantitative results are shown in Table A-1 in Appendix A.) The first three columns of Table 2 depict the outcomes of the 2016 policy, while the last three columns focus on the effects of the 2018 policy. Results in columns 1 and 4 use all mortgages, whereas columns 2 and 5 and columns 3 and 6 examine samples restricted to low-ratio and high-ratio mortgages, respectively.

Table 2: Estimated direct impact of changes in mortgage stress test rules on various outcomes of interest

| Outcomes of interest | 2016 policy | 2018 policy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| All mortgages | Low-ratio mortgages | High-ratio mortgages | All mortgages | Low-ratio mortgages | High-ratio mortgages | |

| Effective total debt service ratio | ||||||

| Number of mortgages | ||||||

| Mortgage size | ||||||

| Credit score | ||||||

| Loan-to-value ratio | ||||||

| Purchase value | ||||||

| Aggregate local house price growth | ||||||

Legend (for a level of statistical significance at 10%):

Note: Data are monthly observations from October 2015 to October 2017 for the 2016 policy and from January 2017 to January 2019 for the 2018 policy.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Teranet-National Bank and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: January 2019

First, we delve into the implications of the 2016 policy, which affected only high-ratio mortgages:12

- Effective TDS ratio—As anticipated, for high-ratio mortgages, geographical areas more exposed to the policy exhibited a more pronounced reduction in average TDS ratios compared with less exposed areas. This confirms that market participants adhered to the policy, as suggested earlier by Chart 2. Conversely, for low-ratio mortgages unaffected directly by the policy, we observe no statistically significant difference in TDS ratios after the policy implementation.

- Number of mortgages and mortgage size—For high-ratio mortgages, areas more exposed to the policy experienced a greater decrease in mortgage issuance than areas less exposed to the change, although we find no statistically significant change in the average loan amount. Concerning low-ratio mortgages, we detect a more substantial increase in both mortgage issuance and average mortgage size in the most exposed areas after the policy implementation. Therefore, the 2016 policy that affected only high-ratio mortgages led to a shift from high-ratio to low-ratio mortgages, with the total number of mortgages and average mortgage size increasing relatively more in the most exposed areas compared with the least exposed areas.

- Credit quality (credit score and LTV ratio)—This policy appears to have enhanced the quality of new borrowers. Across both segments of the mortgage market, average credit scores and down payments increased after the policy was introduced, particularly in the most exposed areas.

- Purchase value and aggregate growth in local house prices—Neither the average purchase value for new borrowers nor the aggregate growth in local house prices decreased in reaction to the policy. In this respect, we find that the 2016 policy had no dampening effect on the mortgage and house price booms in Canada at that time.

In contrast, the outcomes differ significantly when we analyze the 2018 policy affecting the low-ratio segment of the market. Overall, we find that this change successfully slowed down the credit and house price booms. Areas more exposed to the 2018 policy experienced a more pronounced decline in the number of mortgages originated, average mortgage size and aggregate growth in local house prices than less exposed locations did. These patterns hold true for both segments of the market.

Regarding credit quality, the findings for the 2018 policy are more nuanced:

- Effective TDS ratio—For low-ratio mortgages, we find a stronger decline in the effective TDS ratio in the most exposed areas compared with the decline in the least exposed ones. However, for high-ratio mortgages, the effective TDS ratio grew more in the most exposed areas than it did in the least exposed areas.

- Credit quality (credit scores and down payments)—For high-ratio mortgages, after the policy implementation, credit scores and down payments increased more in the most exposed areas than in the least exposed ones. However, for low-ratio mortgages, we observe no statistically significant differential behaviour induced by the policy.

Although the 2018 policy did not directly affect high-ratio mortgages, the improvement in quality within this segment may reflect a shift from low-ratio to high-ratio mortgages for some consumers.13 Moreover, households not able to qualify for the desirable loan under the revised Guideline B-20 may have turned to alternative lenders not bound by federal mortgage standards. This could have undermined the effectiveness of these policies in mitigating systemic financial vulnerability.14, 15

The 2022–23 episode of monetary policy tightening

One goal of the mortgage stress tests is to increase the likelihood that households can withstand potential increases in interest rates or reduction in income and thereby avoid falling into arrears or delinquencies. In this section, we formally assess whether the mortgage stress tests reduce the likelihood of mortgage holders going into a delinquency status when interest rates increase.

As illustrated in Chart 1, between March 2022 and July 2023, the Bank of Canada raised its policy rate from 0.25%, where it had been since March 2020, to 5.0%. We use this episode of significant and rapid monetary policy tightening to analyze the interplay between macroprudential policy and monetary policy. Specifically, focusing on the period from January 2021 to October 2023, we estimate the following empirical specification using ordinary least squares:

\(\displaystyle\, Y_{c,t}\) \(\displaystyle=\, \beta_0\) \(\displaystyle+\, \beta_1\ Disqualified\ Share_c\) \(\displaystyle ×\, MP\ Tightening_t\) \(\displaystyle+\, θ_c\) \(\displaystyle+\, γ_{p,t}\) \(\displaystyle+\, ϵ_{c,t}\) \(\displaystyle\, (3)\)

This specification resembles equation (2). However, the dummy variable is replaced in equation (3) by a dummy variable that takes the value of one between March 2022 and October 2023 (the period of monetary policy tightening) and zero in the time frame preceding the rate hike, from January 2021 to February 2022.

Here,\(\displaystyle\, Y_{c,t}\) denotes local aggregate rates of credit delinquencies (of both 30-plus days and 90-plus days) across various credit products (e.g., mortgages, credit cards and auto loans).16

Once again, the primary coefficient of interest is\(\displaystyle\, \beta_1\). A statistically significant difference of this coefficient from zero would indicate that, during a period of rising interest rates, borrowers in locations more affected by macroprudential policy (i.e., areas with a higher share of people disqualified from getting a mortgage) behaved differently in terms of credit delinquencies than borrowers in less affected areas, relative to the period before the increase in interest rates.

Table 3 reports the qualitative results of estimating the specification in equation (3), and Table B-1, Table B-2, Table B-3 and Table B-4 in Appendix B report the full quantitative results.

Table 3: Estimated direct impact of monetary policy tightening on various types of credit products

| Types of credit products | 30+ days of delinquencies | 90+ days of delinquencies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 2016 policy |

(2) 2018 policy |

(3) Both policies combined |

(4) 2016 policy |

(5) 2018 policy |

(6) Both policies combined |

|

| All credit products | ||||||

| All credit products except mortgages and HELOCs | ||||||

| By product | ||||||

| - Mortgages | ||||||

| - HELOCs | ||||||

| - Credit cards | ||||||

| - Auto loans | ||||||

| - Lines of credit | ||||||

Legend (for a level of statistical significance at 10%):

Note: HELOC means home equity line of credit. Data are monthly observations from January 2021 to October 2023. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.

Sources: TransUnion and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2023

From column (1), we conclude that, because of the 2016 policy, the increase in the local aggregate share of 30-plus day delinquencies during the recent period of monetary policy tightening relative to the prior year was smaller in the most exposed areas than in the less exposed areas. Specifically, we find that during this period, delinquencies grew 3.3 basis points less in the 90th percentile of the disqualified share than they did in the 10th percentile. This corresponds to approximately 19% of the average increase in delinquencies across locations in this period.17

Column (2) indicates that the 2018 policy did not lead to discernible differences in the shares of 30-plus day delinquencies between the most and least exposed areas after March 2022. Column (3) reveals that most of the recent variance in 30-plus day delinquencies across locations can be attributed to the impact of the 2016 policy. When considering individual products, we can see that almost all the decline in delinquencies occurred in segments other than home-secured credit (mortgage and home equity lines of credit), with the main mitigating effect coming from credit cards.

In column (4), we show that the 2016 policy led to a smaller increase in the local aggregate share of 90-plus day delinquencies in areas more exposed to the policy, compared with that for less exposed areas, during the recent period of monetary policy tightening. This result is driven mostly by auto loans. The 2018 policy (column 5) did not lead to sizable differences in the shares of 90-plus day delinquencies between the most and least exposed areas after March 2022. This reinforces the notion that, while the 2016 policy did not manage to halt the credit boom in Canada, it did enhance the credit quality of high-ratio mortgage borrowers, as evidenced by a subdued increase in delinquencies.

Some borrowers may have sought mortgages outside the regulated system in response to the 2016 policy. However, this tightening of macroprudential policy bolstered the overall resilience of the system, particularly in the face of potential increases in the policy rate. Consequently, mortgage rate stress tests have fortified the ability of borrowers, especially those with high-ratio mortgages, to better navigate significant increases in mortgage payments.

Conclusion

Our analysis sheds light on the impact of mortgage stress tests in Canada. We find that the 2018 policy expanding stress tests to low-ratio mortgages had a direct impact on mortgage credit and house prices. We also conclude that the stress tests limited the increase in delinquencies after the recent rise in interest rates.

The 2016 policy, targeting high-ratio mortgages, led to a shift in borrowing toward low-ratio mortgages but did not curb the credit and housing booms. Nonetheless, it improved the credit quality of new borrowers, as evidenced by their higher credit scores and lower debt service ratios. In contrast, by extending the stress tests to low-ratio mortgages, the 2018 policy effectively dampened the credit and house price booms and generally enhanced borrower quality within the regulated market.

Furthermore, our analysis demonstrates that the mortgage stress tests enhance borrowers’ resilience during periods of monetary policy tightening. Specifically, geographical areas more exposed to the 2016 macroprudential policy experienced a lower increase in delinquencies than less exposed areas, particularly in non-mortgage credit products, including credit cards and auto loans.

Overall, our findings underscore the importance of macroprudential policies such as mortgage stress tests. These policies promote financial stability and ensure households can manage increases in mortgage payments without falling behind on their credit obligations, even amid challenging economic conditions.

Appendix A: Regression results from equation (2)

Table A-1: Direct impact of changes in stress test rules

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 policy | 2018 policy | |||||

| All mortgages | Low-LTV | High-LTV | All mortgages | Low-LTV | High-LTV | |

| a. Effective TDS ratio | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.161 (0.114) |

0.219 (0.171) |

-0.885*** (0.095) |

-0.884*** (0.090) |

-0.820*** (0.144) |

0.466*** (0.125) |

| Observations | 9845 | 8996 | 9225 | 9927 | 9196 | 9225 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.126 | 0.087 | 0.107 | 0.107 | 0.089 | 0.177 |

| b. Number of mortgages | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 14.417** (7.200) |

17.586** (8.807) |

-2.506* (1.387) |

-21.206* (11.769) |

-19.616* (11.027) |

-3.345** (1.521) |

| Observations | 10006 | 9414 | 9459 | 10099 | 9650 | 9486 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.918 | 0.920 | 0.853 | 0.921 | 0.928 | 0.848 |

| c. Mortgage size | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 2.352* (1.316) |

2.770* (1.560) |

1.801 (1.169) |

-12.581*** (1.955) |

-14.463*** (2.137) |

-9.090*** (1.249) |

| Observations | 9943 | 9227 | 9388 | 10012 | 9426 | 9392 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.800 | 0.702 | 0.806 | 0.810 | 0.741 | 0.823 |

| d. Credit score | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 1.952*** (0.703) |

1.718* (0.949) |

1.663** (0.806) |

1.476* (0.871) |

1.166 (1.010) |

1.617* (0.866) |

| Observations | 9936 | 9210 | 9381 | 10002 | 9413 | 9386 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.146 | 0.095 | 0.063 | 0.184 | 0.122 | 0.086 |

| e. LTV | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.292* (0.158) |

-0.097 (0.179) |

-0.145*** (0.045) |

0.211 (0.140) |

0.147 (0.170) |

-0.188** (0.077) |

| Observations | 9943 | 9227 | 9388 | 10012 | 9426 | 9392 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.376 | 0.085 | 0.096 | 0.420 | 0.116 | 0.172 |

| f. Purchase value | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 8.873*** (2.229) |

7.432** (2.957) |

3.581*** (1.320) |

-23.557*** (4.011) |

-25.732*** (4.685) |

-9.948*** (1.337) |

| Observations | 9815 | 8923 | 9151 | 9872 | 9119 | 9195 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.803 | 0.716 | 0.776 | 0.809 | 0.753 | 0.808 |

| g. Aggregate local house price growth | ||||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 0.740*** (0.131) |

-2.194*** (0.336) |

||||

| Observations | 2832 | 2856 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 | ||||

Note: Table A-1 reports the estimates of equation (2) for the different dependent variables identified in the table. All regressions include location and province-by-time fixed effects. Standard errors are presented in parentheses and are clustered at the location level. ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. LTV means the loan-to-value ratio and TDS means the total debt service ratio. Data are monthly observations from October 2015 to October 2017 for the 2016 policy and from January 2017 to January 2019 for the 2018 policy.

Sources: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Teranet-National Bank and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: January 2019

Appendix B: Regression results from equation (3)

Table B-1: Share of 30+ day delinquencies

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disqualified share 2016 | Disqualified share 2018 | Disqualified share 2016 and 2018 | |

| All credits | |||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.013** (0.006) |

-0.004 (0.007) |

-0.020*** (0.006) |

| Observations | 14654 | 14756 | 16354 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.919 | 0.922 | 0.907 |

| All credits except mortgages and HELOCs | |||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.014** (0.006) |

-0.005 (0.007) |

-0.020*** (0.007) |

| Observations | 14654 | 14756 | 16354 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.914 | 0.917 | 0.901 |

Note: Table B-1 reports the estimates of equation (3) for the share of 30-plus day delinquency status. All regressions include location and province-by-time fixed effects. Standard errors are presented in parentheses and are clustered at the location level. ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. HELOC means home equity line of credit. Data are monthly observations from January 2021 to October 2023. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.

Sources: TransUnion and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2023

Table B-2: Share of 30+ day delinquencies by product

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortgages | HELOCs | Credit cards | Auto loans | Lines of credit | |

| Disqualified share 2016 | |||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 0.001 (0.003) |

0.008 (0.006) |

-0.012*** (0.005) |

0.001 (0.005) |

-0.006 (0.004) |

| Observations | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.447 | 0.151 | 0.780 | 0.660 | 0.257 |

| Disqualified share 2016 and 2018 | |||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 0.001 (0.004) |

-0.001 (0.008) |

-0.015*** (0.005) |

0.014* (0.008) |

-0.016** (0.006) |

| Observations | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.404 | 0.121 | 0.749 | 0.610 | 0.244 |

Note: Table B-2 reports the estimates of equation (3) for the share of 30-plus day delinquency status. All regressions include location and province-by-time fixed effects. Standard errors are presented in parentheses and are clustered at the location level. ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. HELOC means home equity line of credit. Data are monthly observations from January 2021 to October 2023. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.

Sources: TransUnion and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2023

Table B-3: Share of 90+ day delinquencies

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disqualified share 2016 | Disqualified share 2018 | Disqualified share 2016 and 2018 | |

| All credits | |||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.014** (0.007) |

0.003 (0.007) |

-0.013 (0.008) |

| Observations | 14654 | 14756 | 16354 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.959 | 0.958 | 0.953 |

| All credits except mortgages and HELOCs | |||

| Disqualified share x Post | -0.016** (0.008) |

0.002 (0.008) |

-0.013 (0.009) |

| Observations | 14654 | 14756 | 16354 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.957 | 0.956 | 0.951 |

Note: Table B-3 reports the estimates of equation (3) for the share of 90-plus day delinquency status. All regressions include location and province-by-time fixed effects. Standard errors are presented in parentheses and are clustered at the location level. ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. HELOC means home equity line of credit. Data are monthly observations from January 2021 to October 2023. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.

Sources: TransUnion and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2023

Table B-4: Share of 90+ day delinquencies by product

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortgages | HELOCs | Credit cards | Auto loans | Lines of credit | |

| Disqualified share 2016 | |||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 0.010** (0.005) |

0.010 (0.007) |

-0.010 (0.007) |

-0.025*** (0.008) |

-0.001 (0.007) |

| Observations | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 | 14688 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.781 | 0.446 | 0.912 | 0.771 | 0.519 |

| Disqualified share 2016 and 2018 | |||||

| Disqualified share x Post | 0.015*** (0.006) |

0.015* (0.008) |

-0.024*** (0.009) |

-0.002 (0.011) |

-0.006 (0.009) |

| Observations | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 | 16388 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.725 | 0.399 | 0.896 | 0.759 | 0.480 |

Note: Table B-4 reports the estimates of equation (3) for the share of 90-plus day delinquency status. All regressions include location and province-by-time fixed effects. Standard errors are presented in parentheses and are clustered at the location level. ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. HELOC means home equity line of credit. Data are monthly observations from January 2021 to October 2023. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.

Sources: TransUnion and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: October 2023

References

Acharya, V. V., K. Bergant, M. Crosignani, T. Eisert and F. McCann. 2022. “The Anatomy of the Transmission of Macroprudential Policies.” Journal of Finance 77 (5): 2533–2575.

Bank of Canada. 2018. Financial System Review (June).

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. 2018. “Calculating GDS / TDS.” March 31, 2018.

Crawford, A., C. Meh and J. Zhou. 2013. “The Residential Mortgage Market in Canada: A Primer.” Bank of Canada Financial System Review (December): 53–63.

Peydró, J.-L., F. Rodriguez-Tous, J. Tripathy and A. Uluc. 2024. “Macroprudential Policy, Mortgage Cycles, and Distributional Effects: Evidence from the United Kingdom.” Review of Financial Studies 37 (3): 727–760.

Statistics Canada. 2024. “Survey of Financial Security, 2023.” October 29, 2024.

Yao, I. 2018. “Household Responses to Macroprudential Policy.” Unpublished manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Mila Nikolova for excellent assistance in this study.

Endnotes

- 1. See Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2018) for details on how debt service ratios are calculated for insured mortgages.[←]

- 2. The Big Six Canadian banks are the Bank of Montreal, the Bank of Nova Scotia, the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, the National Bank of Canada, the Royal Bank of Canada and the Toronto-Dominion Bank.[←]

- 3. FSAs are geographical areas identified by the first three characters of their postal code.[←]

- 4. To protect the privacy of Canadians, TransUnion did not provide any personal information to the Bank. The TransUnion dataset was anonymized, meaning it does not include information that identifies individual Canadians, such as names, social insurance numbers or addresses.[←]

- 5. Mortgage payments are assumed to follow an annuity with constant payments.[←]

- 6. Chart 3, panel b reinforces the validity of our approach since there are almost no differences between the two measures of the TDS ratio.[←]

- 7. In addition to evaluating some of the most significant policies in the Canadian mortgage market, this analysis contributes to a growing literature on macroprudential policies and their impact across different economies. For instance, Acharya et al. (2022) find that the 2015 introduction of limits on LTV and loan-to-income ratios in Ireland did not lead to a decline in mortgage issuance but caused a reallocation of mortgage credit from low-income to high-income borrowers and from counties where borrowers are close to the lending limits (typically urban areas) to counties where borrowers are more distant from the lending limits (typically rural areas). This reallocation slowed down house price growth in hot housing markets, mitigating the feedback loop between credit and house prices. Peydró et al. (2024) analyze a 15% limit on the share of new mortgages with high loan-to-income ratios (above 4.5) imposed in 2014 on UK mortgage lenders. They find that this policy led to an overall credit contraction, with stronger effects for low-income households in local areas more exposed to constrained lenders. Despite increases in LTV ratio and average loan size, this policy lowered house price growth in the most exposed areas. Peydró et al. (2024), similar to our analysis, do not focus solely on effects immediately after policy implementation. They also examine how the United Kingdom’s 2014 policy affected economic performance during the downturn induced by Brexit and find that, following the Brexit referendum, which led to a house price correction across the United Kingdom, the 2014 macroprudential policy mitigated house price drops and mortgage default rates.[←]

- 8. The effective TDS ratio is computed using the contractual rate rather than the MQR.[←]

- 9. We exclude the month in which the policy is introduced. For the 2016 policy, the pre-period runs from October 2015 to September 2016, and the post-period from November 2016 to October 2017. For the 2018 policy, the pre-period runs from January 2017 to December 2017, and the post-period from February 2018 to January 2019.[←]

- 10. We cluster all standard errors at the location level.[←]

- 11. We cluster all standard errors at the location level.[←]

- 12. Yao (2018) also analyzes the 2016 policy change and finds a window-dressing behaviour in terms of non-mortgage debt around the time of origination. In other words, borrowers decreased their non-mortgage debt right before applying for a mortgage to decrease their debt-to-income ratios.[←]

- 13. Between October 2016 and December 2017, only high-ratio mortgages were subject to the stress tests. This difference made low-ratio mortgages more attractive, potentially leading some households, who in the absence of the policy would have chosen a high-ratio mortgage, to pick a low-ratio mortgage instead. In January 2018, this advantage of the low-ratio mortgage ended, which may explain the shift from low-ratio to high-ratio mortgages for some consumers.[←]

- 14. See Bank of Canada 2018 for further details.[←]

- 15. As seen in Chart 1, the policy rate increased in 2017 and 2018, coinciding with the expansion of the stress tests to low-ratio mortgages. The combination of fixed effects used in the estimated specification allows us to control, at least partially, for confounding effects between monetary policy and the change in stress test rules. However, if, within a given province, the impact of monetary policy on mortgage originations correlates with the disqualified share, then the magnitude of our estimates can be seen as upper bounds of the policy impacts.[←]

- 16. Delinquencies of 30-plus days refers to accounts with payments past due for more than 29 days but less than 60 days. Delinquencies of 90-plus days refers to accounts with payments past due for more than 89 days, excluding accounts in credit counselling or another payment program, repossession or charge-off. For each credit product and location, we compute the share of the total number of credit products under a given delinquency status.[←]

- 17. The disqualified share is standardized, such that the locations in the 10th and 90th percentiles of its distribution have the values of 1.17 and -1.37, respectively, associated with them. The growth difference in the 30-plus day delinquency between these two locations is 0.013 X (1.174043 – (-1.37557)) = 0.033. The average 30-plus day delinquency rate across locations grew from 2.87% in 2020 to 3.05% in 2023. Therefore, the 3.3 basis-point difference between the locations in the 10th and 90th percentiles corresponds to 19% of the 17 basis-point growth in the average 30-plus day delinquency rate across locations.[←]

Disclaimer

Bank of Canada staff analytical notes are short articles that focus on topical issues relevant to the current economic and financial context, produced independently from the Bank’s Governing Council. This work may support or challenge prevailing policy orthodoxy. Therefore, the views expressed in this note are solely those of the authors and may differ from official Bank of Canada views. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.34989/san-2024-25