Introduction

Good afternoon. It’s a pleasure to be here. Today is, of course, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, celebrated by many franco-Manitobans. Bonne Saint-Jean à toutes et à tous!

When I started as governor on June 3, 2020, the economy was in crisis. It was early in the pandemic and Canada’s unemployment rate was 14%—the highest on record. Inflation was well below the 2% target—actually, it was slightly negative. The immediate priority was to avoid deflation and get the economy back on its feet.

But since 2022, we’ve been fighting a new battle—high inflation. When the economy reopened, the combination of gummed up global supply chains, a strong surge in demand and Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine sent inflation sharply higher. It peaked at just over 8% in June 2022. For more than two years, our focus has been getting inflation back down.

We’ve come a long way. Monetary policy has worked, and it is continuing to work. Since January, inflation has been below 3%, and our measures of underlying inflation have eased steadily. This has increased our confidence that inflation will continue to move closer to the 2% target this year. And earlier this month, we lowered our policy interest rate for the first time in four years.

Low, stable and predictable inflation allows Canadians to spend and invest with confidence. It lowers uncertainty and encourages long-term investment. And it contributes to sustained job creation and greater productivity. This in turn leads to improvements in our standard of living. That’s why price stability is our number one priority.

A key ingredient for price stability is a healthy labour market—one in which Canadians have the jobs they want, employers have the workers they need, and real wages grow in line with productivity. Economists call this maximum sustainable employment—the highest level of employment the economy can sustain without triggering inflationary pressures.

The health of the Canadian labour market is what I’ll talk about today. In the 2021 renewal of our monetary policy framework, the federal government and the Bank of Canada agreed price stability is our primary objective. We also agreed monetary policy should continue to support maximum sustainable employment. Since then, we’ve done extensive work to bolster our analysis of the labour market. We’ve published a new dashboard of labour market indicators and updated our benchmarks for these indicators each year.1

So where are we now? And what’s ahead?

With higher interest rates, spending has cooled, and businesses have scaled back their hiring plans. Strong immigration has also helped the supply of workers catch up with demand, bringing the labour market into better balance. But it’s now getting harder to find a new job. That’s particularly affecting younger workers and newcomers to Canada. And it suggests that the economy now has room to grow without building new inflationary pressures.

If we look at the labour market with a longer-term lens, we see that Canada’s growing, inclusive and well-educated labour force has been a key advantage for our economy. It’s been our primary source of economic growth for the past 25 years, and sustaining this advantage is critical to achieving strong non-inflationary growth going forward.

That’s my speech in a nutshell. If that’s all you need, you can start checking your phone now. But if you’ll stick with me for another 15 minutes, I’ll take a closer look at the health of the Canadian labour market in both the short and the long term.

The labour market cycle

When the pandemic hit and the economy shuttered, three million Canadians were laid off and another two million saw their hours of work cut back. Fortunately, the combination of new vaccines and exceptional fiscal and monetary policy fuelled a rapid labour market recovery—indeed, it was the fastest recovery on record.

But as the economy fully reopened, the labour market moved quickly from recovering to overheated. Demand rebounded rapidly as people tried to catch up on what they had missed through the lockdowns. Businesses scrambled to find workers, and the unemployment rate fell to 4.8% by July 2022—a level not seen since the 1970s. Job vacancies rose sharply, reaching one million vacant positions. Wage growth started to climb as the worker shortage intensified and inflation peaked above 8%. The economy was clearly overheated.

Beginning in March 2022, the Bank of Canada raised interest rates forcefully to cool demand and relieve price pressures. As higher interest rates worked their way through the economy and restrained spending, reports of job shortages began to decline. Job vacancies came down, returning close to their historical average, and inflation eased (Chart 1).2

As vacancies came down, the unemployment rate rose gradually, reaching 6.2% last month. This is just above where it was before the pandemic, when the labour market was operating close to maximum sustainable employment. Here in Manitoba, the unemployment rate in May was 4.9%, still below where it was just before the pandemic started.

Overall, the adjustment has gone well

In November 2022, when we were raising our policy interest rate, I gave a speech about how we expected the labour market to adjust to higher rates and slower growth. I said that while the adjustment wouldn’t be without some pain, it need not involve a sharp rise in the unemployment rate. With vacancies so high, much of the adjustment could come from businesses taking down job postings rather that laying off workers.

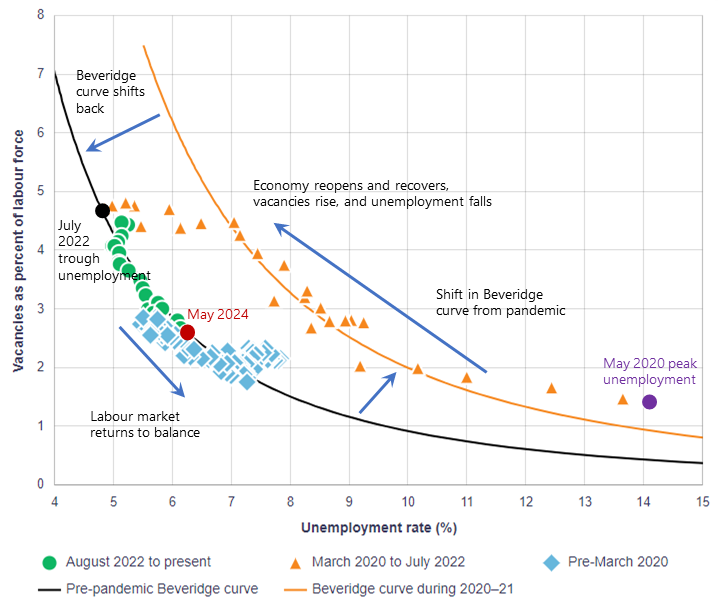

This was based on what economists call the Beveridge curve, which shows the typically inverse relationship between job vacancies and unemployment.3 The evolution of the Beveridge curve is a little complicated. But it provides some insight into why the overall labour market has adjusted relatively smoothly to slower growth (Chart 2). So let me walk you through it.

Chart 2: Job vacancies have declined substantially, and unemployment has edged up

Sources: Statistics Canada, Indeed and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: May 2024

Before the pandemic, the economy was near full employment. Vacancies as a percentage of the labour force and the unemployment rate were both fairly low (Chart 2, cluster of blue diamonds on the black curve).

The pandemic severely disrupted the labour market. The unemployment rate rose rapidly to just above 14% in May 2020 (Chart 2, the purple dot). With this disruption in the labour market, the entire Beveridge curve shifted up and to the right (Chart 2, the orange curve). As the economy gradually reopened, job vacancies rose slightly, and the unemployment rate came down quickly. This is reflected by the movement from right to left along the orange Beveridge curve (Chart 2, orange triangles).

As the economy reopened fully, the Beveridge curve shifted back down. With less disruption, we began to see better matching between job seekers and job vacancies. And we moved from the orange curve back down to the black one. The unemployment rate fell to a 50-year low of 4.8% (Chart 2, black dot), and the economy was back on its old Beveridge curve (Chart 2, black curve).

As we raised interest rates and the economy cooled, businesses started to scale back job postings. And higher immigration helped fill job vacancies. The combined effect saw vacancies decline considerably, moving down the steep part of the Beveridge curve (Chart 2, green dots). We’re now approaching the same part of the curve that we were at before the pandemic—the red dot (Chart 2), which is our latest observation.

What does this recent dynamic mean? When unemployment is very low and job vacancies are very high—as they were when the economy was overheated—the curve is steep. So when you see the green dots moving down without moving much to the right, that means vacancies can come down substantially with only a relatively small increase in unemployment.

This is the soft-landing scenario. It has always been a narrow path, and we have yet to fully stick the landing. Looking forward, the unemployment rate could rise further, particularly as the Beveridge curve is getting flatter. But we continue to think that we don’t need a large rise in the unemployment rate to get inflation back to the 2% target. Inflation is not yet 2%, but it is a lot closer. And with further and sustained easing in underlying inflation in recent months, we are more confident that inflation will continue to move closer to the target.

Turning to wage dynamics, when the labour market was tight and inflation was high, wage growth increased. Depending on the measure you look at, wage growth peaked at between 4½% and 6%. This was roughly twice the pre-pandemic average of 2% to 3%. With inflation now much lower and the labour market rebalancing, we are starting to see evidence that wage growth is moderating. The latest numbers on a six-month basis suggest wage growth has eased to about 4%. This is clearly down from the peak, but still above the pre-pandemic average (Table 1).

The fact that wages are moderating more slowly than inflation is not surprising: wages tend to lag adjustments in employment. Going forward, we will be looking for wage growth to moderate further.

In assessing the implications of wage growth for labour costs and inflation, it is important to separate out wage gains that reflect productivity improvements. Wage gains that are backed by productivity gains do not increase unit labour costs or inflationary pressures. In recent years, the number of higher-paying jobs has grown more than low-wage jobs, which means that overall wage growth has been higher. To the extent that this reflects workers gaining valuable new skills or finding jobs that better match their skills, it should not add to unit labour costs and inflation. So when assessing the inflationary implications of wage growth, we place more weight on wage measures that try to control for occupational shifts (the fixed-weight measure from the Labour Force Survey) or labour cost measures (like unit labour costs). These are running a little lower than other wage measures, particularly when using the more timely six-month rate of change.

| Peak since 2022 | Most recent growth (year over year) | Momentum (Six months, annualized) | Average growth (1998–2019, year over year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable-weight measures (Labour Force Survey) | 5.7% | 5.1% | 4.4% | 2.8% |

| Fixed-weight measures (Labour Force Survey) | 5.0% | 4.5% | 3.3% | 2.6% |

| Average hourly earnings (Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours) | 4.6% | 3.8% | 4.1% | 2.5% |

| Compensation per hour worked (Productivity accounts) | 4.9% | 4.6% | 3.5% | 3.0% |

| Unit labour cost | 6.1% | 5.4% | 3.9% | 1.9% |

But the cooling in the labour market has affected some more than others

So that’s the broad adjustment in the labour market—a reasonably smooth cooling. But the aggregate masks some important differences. Some workers are feeling the slowdown more than others. Employers may not be laying off workers in large numbers, but less hiring over the last year means it’s harder to find that first job. That hurts new graduates and younger workers as well as newcomers to Canada.

Let me take a moment to dig into some detail.

The unemployment rate for newcomers is rising much faster than the overall unemployment rate (Chart 3). Newcomers are taking longer to find a job. This is hard on them—integrating into the Canadian economy is becoming more difficult. It also suggests the government has some room to slow the growth of non-permanent residents without tightening the labour market too much and causing significant labour shortages.

Youth employment, too, has been softening (Chart 4). Again, the evidence suggests that people established in their jobs are not experiencing much of an increase in unemployment. But with fewer job vacancies, it’s taking longer for young people entering the labour market to find a job, and their unemployment rate has risen. It's now about 2 percentage points above its pre-pandemic average.

Labour market adjustments are never evenly distributed. And monetary policy can’t target specific parts of the labour market. But as we set monetary policy, the Bank needs to looks beyond the aggregate to understand what the cooling in the labour market means for different people. The overall unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic levels and still relatively low. But the slowdown in hiring has led to increases in unemployment for younger workers and newcomers to Canada. These workers are feeling the effects of slower growth more than others, and we need to recognize this.

This matters for monetary policy because it indicates there is some slack in the labour market. That suggests the economy has room to grow and add more jobs without creating new inflationary pressures. It also matters for household financial stress. People who find it hard to get a job often find it hard to keep up with their credit card and other debt payments. Many indicators of financial stress declined during the pandemic, but they are now back up near pre-pandemic levels. And late payments on credit cards and auto loans are above pre-pandemic levels. We see this stress particularly among renters.4 These are often younger workers and newcomers.

The labour market and long-run growth

Let me now shift gears and turn to the longer run.

For years, Canada’s biggest economic advantage has been its labour force, which includes people with jobs and people looking for work. Growth in employment in Canada has been much stronger than in the United Kingdom, the euro area and even the United States.5 And this was true before the pandemic and through the pandemic recovery (Chart 5).

Our labour force advantage reflects three key strengths: high labour market participation, strong immigration and a good education system. Let me take each of those in turn.

First, Canada’s labour force participation is stronger than in these other economies. Our participation rate for women is at the top of the G7, helped by affordable child care and flexible work arrangements.

Second, Canada attracts some of the world’s best and brightest students and workers, and we integrate them relatively quickly into the Canadian economy.

And finally, our education system does a good job overall of developing the workers that the economy needs and businesses want to hire. Our post-secondary attainment level is the highest among advanced economies, although we trail the United States in the attainment of advanced degrees.

Our Achilles heel is productivity. We have been very good at growing our economy by adding workers. We have been much less successful at increasing output per worker. And this is catching up with us. While we managed to make up for our productivity under performance from 2000–19 with strong labour force growth, since the pandemic, Canada’s GDP growth has been weaker than in the United States (Chart 6).

As my colleague Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers highlighted in March, weak productivity growth in Canada is a long-standing issue and it’s reaching emergency levels. As good as we have been at growing our economy by adding workers, we need more than one engine.

Moving forward we need to play to our strengths—growing our labour force— while we tackle our weaknesses—investment and productivity.

We should not take our labour market advantages for granted—we need to maintain and build on them. That means continuing to improve the accessibility of child care. It means concerted efforts to improve the labour force participation of groups that have traditionally been left out. I’m thinking especially of Canada’s Indigenous peoples—a growing pool of young talent who have been excluded from economic opportunities for too long. It means aligning immigration to long-standing labour shortages in key areas like skilled trades. It means properly recognizing the credentials, qualifications and experience of immigrants. And it means sustaining and enhancing our education system, and ensuring it is developing students for the jobs of the future.

Tackling our productivity weakness will be harder but it is vital. Productivity growth ensures our businesses are competitive in international markets. It pays for higher wages and underpins rising living standards. And with an aging population and limits to how many immigrants we can successfully absorb each year, improving our productivity growth will become more important to sustaining trend growth.

On the surface, the cause of low productivity growth in Canada is clear enough. On average, businesses here invest much less per worker than they do in the United States. With less investment in machinery and equipment, particularly information and communication technology, workers in Canada have less and older machinery and computers to work with. And weaker investment in intellectual property means they have fewer new innovations to help them work faster, smarter and more efficiently.

The deeper question is why have we had systematically less investment in Canada than in the United States? Or, to put this question in the positive: How do we make Canada more investable? Finding answers to these questions is critical if we want to increase the non-inflationary growth rate of the economy and raise the standard of living of Canadians.

Conclusion

It’s time for me to conclude.

Price stability is our primary mandate, and a healthy labour market and price stability go hand in hand. If employment is well below its maximum sustainable level, the economy is missing jobs and incomes, and this puts downward pressure on inflation, pushing it below the 2% target. That’s what happened early in the pandemic. When the economy is operating above maximum sustainable employment, businesses aren’t able to find enough workers to keep up with demand, which puts upward pressure on prices and pushes inflation above the target. That’s where we were in 2022.

Today inflation is much closer to the 2% target. And with some slack in the economy, there is room for the Canadian economy to grow and add more jobs even as inflation continues to move closer to the target. We are not yet back to 2%, and we can’t rule out new bumps along the way. But increasingly, we look to be on our way. Assessing the health of the labour market from various angles is an important input into our monetary policy decisions.

Beyond the near term, a healthy labour market is critical to strong non-inflationary growth in Canada. We have been successful at expanding our economy by growing our labour force. To sustain this advantage, we need to keep investing in an inclusive labour market, smart immigration, and a strong and accessible education system. Let’s not take these for granted as we tackle our productivity problem.

Thank you.

I would like to thank Daniel de Munnik, Marc-André Gosselin and Shu Lin Wee for their help in preparing this speech.