Introduction

Good afternoon, and thank you to the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce and the Associates of the Asper School of Business for supporting this event and giving me the opportunity to speak with you today. And thanks to all of you for choosing to spend your lunch hour with me.

It’s a particular pleasure for me to be in Winnipeg. I still consider this city—and this province—to be home. I was born here, grew up here, attended university here and started my career here. And I still have a lot of family, friends and former colleagues in Manitoba, so this feels a bit like a homecoming for me.

Yesterday was International Women’s Day, and I had the opportunity to meet with an inspiring group of women leaders from across this province. Today I am looking forward to hearing from you.

The Bank regularly surveys Canadian consumers and businesses as part of our work. But having the chance to hear from you directly about how your communities and businesses are navigating economic decisions day-to-day is very important to us. We know the decisions we make have a real impact on people.

And I do plan to spend some time discussing the Bank’s decision yesterday to hold interest rates steady and letting you in on our thinking as we made that decision. But let’s start by setting the scene. I’ll begin with inflation because that’s what we target. We can all agree that it’s still too high. It has started to come down, but, at 5.9%, we still have a way to go to get back to our 2% target.

Our monetary policy is working to do just that. Increases in our policy interest rate are starting to slow demand, giving supply time to catch up and taking some of the pressure off prices.

We know that adjusting to higher interest rates has been hard for many Canadians. Our policy rate is at levels not seen for 15 years. We also know that many Canadians are asking how making their mortgage more expensive while they’re dealing with higher grocery bills will eventually lower inflation and make their lives easier.

We’re also often asked how raising interest rates will solve inflation if it is primarily a global phenomenon. Since it was big global forces—surging commodity prices and major supply chain disruptions—that helped spark inflation in the first place, what can the Bank really do about it?

These are good questions, and I am going to do my best to answer them today.

I’ll explain how high inflation in Canada largely took root due to global factors that pushed up prices for many commodities and other goods.

Then I’ll talk about how inflationary pressures spread in Canada because of strong domestic demand, in other words, an overheating economy. This is what we’ve been addressing with higher interest rates.

After that, I’ll go over what we’re seeing globally and at home to put things into a broader perspective.

Finally, as I mentioned, I’ll talk about what led us to our decision yesterday.

How high inflation took hold in Canada

Global forces

Without question, one of the biggest drivers of high inflation around the world has been higher commodity prices. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck and the global economy abruptly shut down, many commodity prices plummeted—especially oil prices, but prices for natural gas, lumber and copper also fell. However, some sectors of the economy, such as housing, recovered quickly. So demand for some related commodities, such as lumber, bounced back very fast. And then, as things started to open back up, demand and prices for other commodities, such as oil and natural gas, recovered quickly too.

Then, in early 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further upended the global economy. The Ukrainian diaspora in Canada is the world’s second largest, and Manitoba has the highest concentration of Ukrainian-Canadians in the country. So I know the human toll of this senseless war has been felt here. The economic impacts have also been far-reaching and damaging. By the middle of last year, global commodity prices—particularly for oil, natural gas and wheat—had surged to levels not seen since 2008, right before the global financial crisis.

It didn’t take long for Canadians to feel the effects. Gasoline prices soared to well above $2 a litre last summer. And because commodities are key inputs to so many products, the impact on prices was broad-based. Higher energy prices raised the operating costs of virtually all businesses. They also raised the cost of shipping goods to customers. Food prices soared too. The war in Ukraine affected the prices of grain and fertilizer. Weather events in other parts of the world affected the supply of many crops. And disease restricted the supply of poultry and eggs. This perfect storm of factors was showing up in Canadian grocery stores by the middle of last year.

The other main driver of high inflation around the world has been a combination of disruptions in global supply chains and a spike in demand for durable goods.

Like other people around the world, many Canadians upgraded their homes during the pandemic with things like new furniture, appliances and technology. We couldn’t spend on services—like vacations and restaurants—so most of our spending, and the spending of many others around the world, was going to goods. Meanwhile, lockdowns were wreaking havoc on highly integrated global supply chains. Factories were shut down, raw materials were in short supply, and transportation backlogs piled up. The result was prices for a wide range of goods spiked.

Domestic demand

These three global inflationary forces—a spike in commodity prices, a surge in global demand for goods and impaired supply chains—then ran into a fourth element: an overheating economy here in Canada.

Early last year, around this time, we were coming out of the Omicron wave of COVID-19 and what may turn out to be the final lockdown. The Canadian economy had become increasingly resilient over the course of the pandemic, weathering each subsequent lockdown better than the last. Canadians were anxious to catch up on the things they had missed, like travelling and eating out, so we saw some spending start to shift from goods back to services.

And even though Canadian businesses had shown remarkable resilience adapting to multiple lockdowns, many struggled to keep up with the surge in demand they faced. Supply chain issues were still with us, and staff who had left or been laid off during the pandemic had to be rehired, re-trained or replaced. Our survey of businesses in the first quarter of last year found that four out of five would have trouble meeting an unexpected boost in demand—a record high.1

This pressure showed up very clearly in the labour market. The number of vacant jobs rose to nearly twice the pre-pandemic level, an obvious sign of widespread labour shortages. Labour is an important input cost for businesses, particularly in the services sector. This shortage of available workers, combined with the surge in demand for services, put upward pressure on services prices.

In addition, with demand increasingly strong, many businesses began passing higher costs onto their customers. Price increases were both larger and more frequent than normal.

Getting inflation under control

So that’s how global and domestic forces combined to push inflation in Canada up to 40-year highs. But just as inflation rose around the world, it’s now retreating in a fairly consistent pattern.

And just as they were on the way up, commodity prices have so far been a key contributor on the way down. Oil prices have declined by around 35% since last summer, mostly due to a better outlook for supply. More recently, natural gas prices have fallen sharply too—by around 60% since autumn—largely because winter in the northern hemisphere has been warmer than usual. Prices for forestry, metal and agricultural commodities have also softened. Lower energy prices, in particular, are translating into lower costs for both global shipping and inputs.

Global supply chains are also improving. There are fewer of the bottlenecks that made it so hard for the global supply of commodities and other goods to keep up with demand. Shipping costs and delivery times are both approaching pre-pandemic levels.

And monetary policy is doing its job. Central banks around the world have tightened policy by raising interest rates, restraining some of the domestic factors behind inflation in different countries. That’s resulting in slower growth in global demand overall, especially for durable goods.

The Bank of Canada is no exception. We raised the policy rate eight consecutive times starting in March 2022. Our higher interest rates are starting to slow growth in household spending, particularly in sectors that are sensitive to interest rates. And, overall, higher rates are helping to rebalance demand and supply.2

That being said, a broad range of labour market indicators have shown only modest signs of easing to date. Job vacancies have come down a little but are still elevated, the unemployment rate is near historical lows, and many businesses continue to report labour shortages.

So what does all this mean for inflation? Well, as I said at the outset, inflation eased to 5.9% in January from a high of over 8% last summer. It’s still too high, but our most recent forecast in January has it slowing steadily to around 3% in the middle of this year and reaching the 2% target next year.3

So the inflation story here in Canada has some symmetry so far: global and domestic factors combined to drive inflation up, and both will need to retreat further to get us back down to the 2% target.

Canada’s experience in a global context

So far, I have talked a lot about how Canada’s experience had a good deal in common with other countries. But we can also see some differences. So let me spend a few minutes comparing where we are on a few dimensions relative to some of our counterparts.4

Our current rate of inflation, while still too high, is the second lowest in the G7 advanced economies.5 Japan’s is lower, at 4%. And momentum in inflation, as measured by the rate of change in prices over the past three months, has also been close to the bottom of the G7. It’s also important to note that services price inflation in Canada has levelled off in recent months, while it has continued to rise in some other countries. These rankings could move around a little in the coming months, of course. But they’re all rankings where being near the bottom is a good thing.

Let me turn to economic performance: Canada has recorded the strongest growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in the G7 since the tightening cycle began early last year. And the International Monetary Fund expects Canada to have the strongest average GDP growth in the G7 over 2023 and 2024.6 That’s good news, but it underscores that our interest rate increases still need to work their way through the economy to ensure demand cools enough for supply to catch up.

Our employment growth has also been strong compared with most of the G7. We’ve had the second-strongest recovery in jobs and hours worked since the start of the pandemic. We’ve also had the fastest adult population growth, fuelled by immigration. And our labour force participation rate for women is at the top of the G7, helped by more affordable child care and flexible work arrangements. More supply of labour is a good thing because it usually means the economy can grow more with less inflationary pressure.

However, we continue to have one of the lowest rates of productivity growth in the G7. Productivity growth is a good thing for the economy because it allows businesses to pay for higher wages. If we continue to see the above-average wage growth that we’ve been seeing in Canada without stronger growth in productivity, it will be difficult to bring inflation all the way down to 2%.

Households in Canada are also some of the most indebted in the G7: our household debt-to-income ratio has been on a generally upward path for the past three decades. High debt typically makes an economy more sensitive to interest rate increases.

When it comes to monetary policy, Canada has had one of the most forceful tightening cycles. We were the second major central bank in the advanced economies to raise interest rates to fight inflation. And the total increase to our policy rate, 425 basis points, is second only to the US Federal Reserve’s 450 basis points. We were also the first to end quantitative easing. As well, since we began quantitative tightening, our balance sheet has contracted the fastest—by more than 20%—complementing the restrictive stance of our policy rate.

As global inflationary pressures continue to recede, each country will need to chart its own course to get back to price stability. Canada, like other countries, has unique circumstances that will affect the path of the economy and inflation. But that’s the advantage of an independent monetary policy: We can get back to our inflation target of 2% in a way that makes sense for us, just as other central banks are doing for them.7

Let me now turn to our decision yesterday and how these and other factors shaped the Governing Council’s thinking.

Our decision yesterday

As I just mentioned, we raised interest rates forcefully in response to high inflation.

And, after having front-loaded our policy tightening by doing a lot in less than a year, we said in January that we expected to pause and assess the impact of those moves.

Yesterday, we decided to leave the policy rate at its current level of 4.50%. We also continued our policy of quantitative tightening.

It’s a conditional pause, though. If economic developments unfold as we projected and inflation comes down as quickly as we forecast in the January Monetary Policy Report (MPR), then we shouldn’t need to raise rates further. But if evidence accumulates suggesting inflation may not decline in line with our forecast, we’re prepared to do more.

Looking at the data since January, Governing Council found a mixed picture. Overall, though, things are unfolding broadly in line with our outlook.

We’ll need to see more evidence to fully assess whether monetary policy is restrictive enough to return inflation to 2%. For now, let me unpack recent developments and share some insight into what we discussed and how we’ll be thinking about things going forward.

I’ll start with economic activity. Growth in the fourth quarter of 2022 slowed more than expected, coming in flat. With consumption, government spending and net exports all increasing, the weaker-than-expected GDP was largely due to a big slowdown in inventory investment. The data did show that, in general, higher borrowing costs continue to weigh on sectors that are sensitive to interest rates, such as housing. They also showed that business investment has weakened as demand slows both in Canada and abroad.

We talked a lot about the labour market. Job gains in Canada have been surprisingly strong in recent months, and the labour market remains very tight. With weak economic growth for the next couple of quarters, however, we expect that the tightness in the labour market will ease and, as it does, pressure on wages will come down. You may remember me saying if strong wage growth isn’t accompanied by strong productivity growth, it will be hard to get to 2% inflation. Well, we noted that data last week showed labour productivity in Canada fell for a third straight quarter, so productivity isn’t trending in the right direction so far.

We agreed inflation is coming down largely as expected and that there has been a clear momentum shift in goods prices. But we also agreed services price inflation needs to cool further—beyond the levelling off I mentioned. And we will need to see companies return to more normal pricing behaviour. Year-over-year and three-month rates of core inflation will both need to come down more than they have for inflation to return sustainably to 2%, as will short-term inflation expectations.

I spent some time earlier on the global backdrop, so let me tell you what we talked about on that front. We noted that in the United States and Europe, near-term outlooks for growth and inflation are now somewhat higher than we expected in January. In particular, labour markets remain tight and core inflation is still high. Since these are our main trading partners, this could point to some further inflationary pressure in Canada. We also noted that a key risk to our projection—an increase in global energy prices—hasn’t materialized so far. But China’s economy is rebounding, as expected, now that it has reopened. The strength of China’s recovery and the ongoing impact of Russia’s war on Ukraine remain key sources of upside risk for commodity prices, including energy.

And with inflation still well above our target, we’re still more worried about upside risks.

We’ll have more to say about all of this in our April forecast.

Conclusion

I hope I’ve given you a sense of how global forces have influenced the growth of prices here at home and how they will continue to influence inflation going forward. Major economies around the world are highly interconnected—but while we’re always thinking globally, we have to act locally. We must tailor our policy to Canadian circumstances. And monetary policy needs to be forward-looking.

We’re watching closely to see how things unfold. And we are committed to getting inflation all the way back to 2% so Canadians can once again count on low, stable and predictable inflation with sustainable economic growth.

Thank you.

I would like to thank Subrata Sarker and Fares Bounajm for their help in preparing this speech.

Related information

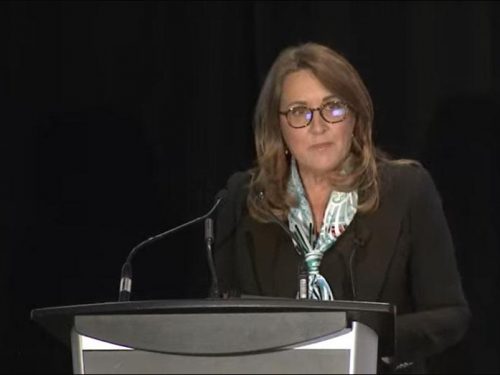

Speech: Manitoba Chambers of Commerce

Economic Progress Report — Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers speaks before the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce (13:55 (ET) approx.).

Media Availability: Manitoba Chambers of Commerce

Economic Progress Report — Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers takes questions from reporters following her remarks (15:10 (ET) approx.).